New Directions in Music Song Remains the Same Series

by Marshall Bowden

Released in the summer of 1967, “Ode to Billie Joe” demonstrates how a good story can become more real than our own lives.

There was plenty going on that summer: the Monterey Pop Festival, Elvis married Priscilla, Richard Speck was executed, race riots raged across the country, the Vietnam War continued. The Doors released their debut album, Hendrix released Are You Experienced. Oh, and the Beatles dropped an album called Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band. No one expected “Ode to Billie Joe,” the debut single by newcomer Bobbie Gentry, to make much of a splash.

But for a time, all America became obsessed by the question of what happened on Choctaw Ridge that caused Billie Joe McAllister to commit suicide by jumping off the bridge. Like Who Shot J.R.?, “Ode” became one of those cultural memes that spread like wildfire. Everyone wanted to know what the narrator and Billie Joe tossed off that same bridge: your third period teacher, Dad’s barber Luke, Grandma, the cop directing traffic. Maybe even Bob Dylan.

Dylan and The Band were holed up in West Saugerties, NY, living a lifestyle that revolved around making music and living in a small town. It was simpler and quieter than living in the city, more insular in the way that small towns are. Culturally small towns are more similar to each other, regardless of geographic location, than they are to larger towns and cities that are closer to them. In other words, the distance between West Saugerties and Tupelo is not as great as many people would imagine.

Who Was Bobbie Gentry?

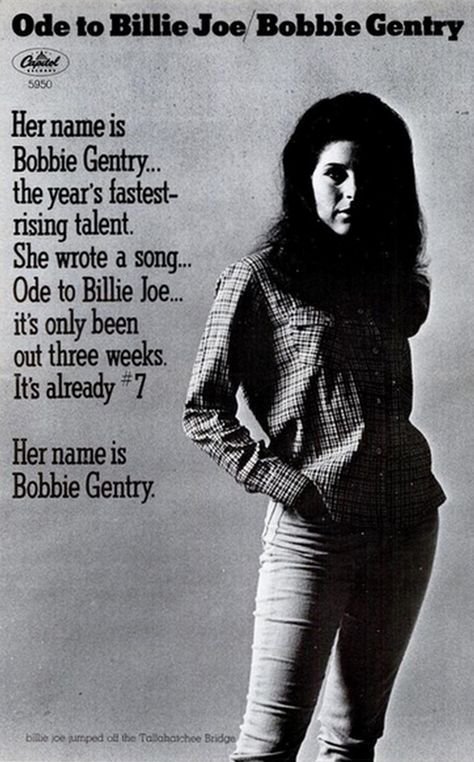

Bobbie Gentry had kicked around the music business for awhile before she was signed by Capitol Records on the strength of her demo recordings, “Ode to Billie Joe” being one of them. She was smart, talented, practical–and a woman in an industry that has always been blatantly sexist and a hotbed for sexual harassment. Gentry managed success not only as a performer, but also as a songwriter and producer, and later as a television producer, but it would be foolish to think that she got there without a strong taste of all the crap that the music industry can throw at a performer, especially a female one. One has only to look at her publicity photos to see the sexpot marketing that was de rigeur for any female artist at the time. But she was sharp and she played the game well, and dealt herself a winning hand.

After her Capitol years, in the early 1970s, Gentry was one of the three hottest acts in Vegas, the others being Elvis Presley and Tom Jones. Gentry not only performed her Vegas shows, she designed many of the costumes and put together the shows. She was a savvy businesswoman as well, owning her own publishing rights, investing in the Phoenix Suns, and receiving a nice payout for the rights to make a film version of her biggest hit.

Then in the early 80s she suddenly went off the grid. Walked off into the sunset and was pretty much never heard from professionally again. It was a big mystery that periodically gets revived, most recently in 2016 when a Washington Post reporter claims to have tracked her down to a house in a gated community not far from the site of “Ode to Billie Joe.” What could have happened? Why did Gentry leave such a successful career behind?

We can’t claim to know for certain, but I’d lay dollars to donuts that she simply got tired of being a talented and successful woman who was constantly treated as a know-nothing one hit wonder or a sex object. Of course she was tough and she had confidence in her abilities and she damn well proved herself out there onstage and in the studio. But that kind of thing can wear at a person and make them bitter. She had all the money she would need and she could make more with smart investments. She didn’t open a chain of restaurants or a music club or invest in an As Seen on TV gadget she could market. She pulled the plug on her public persona and walked out into the rest of her life.

Maybe she saw that the future would be increasingly bleak for any woman in the public eye in a culture that was increasingly youth obsessed. Or maybe she just saw what happened to Elvis. But it seems fairly clear that the industry probably had a lot to do with it.

The Secret World of “Ode to Billie Joe”

Southern Gothic seeks to use the grotesque as a stand in for the past, for the things that everyone knows, the secret history, where the bodies are buried. These things lurk beneath the surface of the everyday, the mundane. If we were to acknowledge them, we believe, then the life we live, the culture we represent, the relationships we have with each other would all collapse under the weight of something so horrible that we repress it at all costs.

According to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Literature: “Rather than a sensationalist freak or horror show, grotesque literature cuts through the veil of civility, through decorum and oppressive normative fabrications to expose a harsh, confusing reality of contradictions, violence, and aberrations.”

“Ode to Billie Joe” makes use of one of Southern Gothic’s biggest tropes–the secret, often a dark family secret that everyone knows but no one talks about. Sometimes there are hints of madness or betrayal or just plain bad luck. A curse: “Seems like nothing ever comes to no good up on Choctaw Ridge.”

There is a secret, the narrator’s secret. She knows what happened on Choctaw Ridge . She may know the reason for his suicide. There’s a sense that she mourns Billie Joe, mourns the loss of something between them–“mama said to me child, what’s happened to your appetite.” No one else mourns the dead boy or expresses any real sense of loss over his death.

Gentry has said, when asked about what the couple were seen throwing off the bridge in the song, that it really didn’t matter. Because the point of the song was the casual indifference with which the family relayed the news of Billy Joe’s death and discusses it without really discussing it:

“Everybody has a different guess about what was thrown off the bridge—flowers, a ring, even a baby. Anyone who hears the song can think what they want, but the real message of the song, if there must be a message, revolves around the nonchalant way the family talks about the suicide. They sit there eating their peas and apple pie and talking, without even realizing that Billie Joe’s girlfriend is sitting at the table, a member of the family.”

http://performingsongwriter.com/bobbie-gentry-ode-billie-joe/

But it seems that maybe they do know. Or they have hunches and drop hints. The narrator’s brother asks if she wasn’t talking to Billy Joe after church last Sunday night. Her mother mentions that the preacher “said he saw a girl that looked a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge/And she and Billie Joe was throwing somethin’ off the Tallahatchie bridge.”

So the ultimate cruelty it seems, is that the family all suspects or knows something happened and that it involved their daughter or sister, but they react nonchalantly. They act as if they did not know and their silence makes it impossible for there to be any dialogue. The mundane helps get us through horrific events, but it also robs us of our ability to really experience our emotions. A big event has occurred but there is no reckoning. Nothing is revealed.

The final verse reveals that in the year since the suicide of Billie Joe the narrator’s family has scattered. Her brother has married and moved away. Her father has died and her mother is deep in a depression. And the narrator? She spends a lot of time on Choctaw Ridge throwing flowers from the bridge into the muddy water, like Shakespeare’s Ophelia in a dream world of sadness and longing.

The Basement Tapes: Making Music Off the Grid

The recording industry and the machinations of stardom were also responsible for Bob Dylan’s reclusive 1967 disappearing act. His 1966 tour with The Hawks (soon to become The Band) was an increasingly hostile event, with Dylan facing anger and resentment not only onstage but also in interviews and press conferences. The constant jeering during the electric half of the set took its toll on Dylan and the musicians.

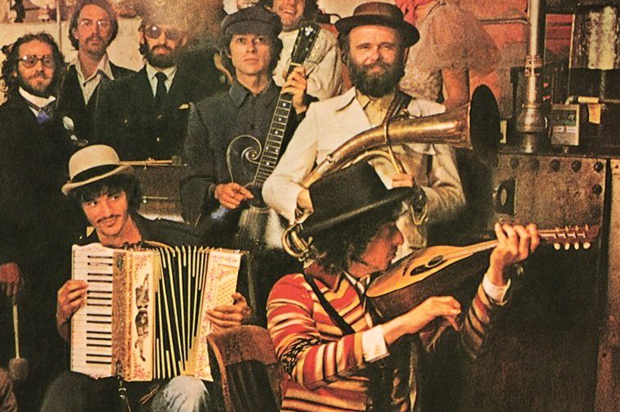

On a break from the tour, Dylan drove his motorcycle off the winding road in upstate New York, and he took advantage of the need to convalesce by cancelling his remaining gigs for the year and settling into rural life with his new wife, Sara. The Woodstock neighborhood had also drawn The Band and Van Morrison. Soon Dylan was recording new songs and old, traditional ballads and folk songs with The Band in the basement of the house the group had rented.

The result was amazing music that was never intended to be released. Some of the songs were intended as demos for other artists to record, and some were just in-jokes or half-baked attempts to reach an arrangement on a traditional song. Garth Hudson, the group’s organist and technical wizard set up a four track recorder and tried to record the songs like they sounded if you were sitting down there in the basement with them. No production whatsoever.

And so Dylan and The Band recorded the track “Clothesline Saga” which was listed on a master tape as “Answer to Ode.” Given the time frame of the recording, the Ode in question is certainly “Ode to Billie Joe.” In it, Dylan rambles on in a ‘story’ about how a family is sitting around waiting for the clothes to dry on the line. There is an attempt at some banal conversation, then the clothes are again checked for dryness. Next morning, the family is out checking on the clothes when the neighbor comes by and relates that the Vice President has gone mad the evening before. “Well there’s nothing we can do ” the narrator assesses. There is a bit of existential dialogue with the neighbor and then the narrator goes inside “And I shut all the doors.”

There is a lazy belief that “Clothesline Saga” is a parody of “Ode to Billie Joe” or an answer record. It’s not a true answer record since it addresses none of the characters or circumstances of the Bobbie Gentry song, It’s probably a little bit affectionate parody, or maybe more of a parody of the country’s near-obsession with the song. If one looks at “Ode to Billie Joe” as a Zen koan, it becomes clear that “Clothesline Saga” is an existential take on how the mundane covers a river of emotion.

Dylan, writing and hanging out in upstate New York, probably heard the song on the radio, possibly multiple times. As a songwriter, a wordsmith, he’s got to be interested in the way the song paints a picture, the way the story is altered by what’s depicted and what’s left out. And he may very well have heard people talking about the song in shops and public spaces, as he went about his regular business.

The clothesline is a fixture of old rural America, a part of a ritual of housekeeping that is woven into the fabric of daily life. The title is ironic since we picture people talking, sharing gossip and juicy information across the clothesline but the real saga is the everyday act of hanging the clothes out and checking to see if they are dry. Events occur–sometimes banal and sometimes seemingly of great import, but we continue to perform our rituals, our daily tasks because that is what is before us here and now. As in “Ode to Billie Joe”, an event has occurred but there is no reckoning.

Not to take all of this too seriously, Dylan is definitely having a bit of fun, and the song is a kind of cosmic joke. “Yep” he seems to say, “I’m out here just playing some music with friends and waiting for the clothes to dry.”

Dylan’s sabbatical was short lived as he was back in the recording studio by year’s end. But he may have been more influenced by “Ode” than is commonly imagined. His songwriting was different from that on his 1965 albums like Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde: less psychedelic and surreal with less emphasis on wordplay. After 1967 his lyrics became simpler in many ways, but he also wrote more narrative songs that sketched out stories without providing too much detail. A song like “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” from Blood on the Tracks is more similar to “Ode to Billie Joe” than it is to “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Bobbie Gentry and Bob Dylan both seemed to find the music business a constraining environment for songwriting and music making and both found a way out of the box. In the Summer of Love their creative paths crossed and, like so many events of that summer, created ripples in the pond that resonated far beyond .

Related Articles:

Upstairs, Downstairs: Revisiting ‘The Basement Tapes‘ by Simon Harper

The Secret Life of Bobbie Gentry by Tara Murtha

Interesting take but it is documented that Dylan pretty much hated Ode to Billie Joe. I found it a vicious parody; a stupid stink bomb that this great man took delight in throwing. Tara Murtha agrees. There is a not so subtle mocking of the conversational style of Bobbie Gentry’s writing. Ask your self this question. If Dylan found, Ode to Billie Joe, so profound, why did he never include it in his books on songs and songwriting? Bobbie Gentry and her cannon of songs has stood the test of time. When her box set was released in 2018, The Girl From Chickasaw County: The Complete Capitol Masters, demand was so great it went through multiple pressings and sold 20,000 sets at nearly 100 dollars a piece. Ode has sold 50 million records on over 100 covers. Her classic story song , Fancy, has passed the 25 million sales mark on a score of covers.

I think you’re right. Dylan’s original title for the song was “Response to the Ode.” Pretty clear.

By the way, OP, Richard Speck was never executed. He was sentenced to death but his sentence was commuted to, effectively, life in prison. He died of a heart attack in the Joliet prison hospital in 1991.

^^^^

Correction; “Answer to the Ode”