Ginger Baker passed away recently after a brief hospitalization, leaving Eric Clapton as the only surviving member of Cream, with Jack Bruce having passed in 2014. There have, of course, been many memorials and career overviews, many of them touching on Baker’s prominence as a jazz drummer as well as having worked with Nigerian Afropop musician Fela Kuti in the early ’70s.

Baker’s rock oeuvre is well known–Cream, Blind Faith–though Baker claims never to have played rock, insisting that his drum style was influenced mainly by jazz. Playing a double bass drum setup with a fiery and aggressive attack, he also led the proto-fusion band Ginger Baker’s Air Force, a group whose name is probably better known than its music.

Among rock aficionados and critics, Baker has long been held at the top of the drum pantheon along with Keith Moon and John Bonham, although he had little time for Moon, who he termed ‘a basher.’ Indeed, Baker’s playing is much cleaner and while there are explosions of kinetic energy, they seem to arise in more organic from Baker’s playing and to dissipate just as quickly.

Baker famously worked with Fela Kuti in the early 1970s, and can be heard on the albums Why Black Man Dey Suffer (1971), Live! (1972) and Stratavarious (1972). Baker was no dilettante. His interest in African music was deep and he continued to work and experiment with its rhythms throughout his life and musical career. Baker’s reason for being in Africa was to build a state of the art recording studio, a difficult and trying process documented in Tony Palmer’s film Ginger Baker in Africa.

He revisited the Afrobeat sound with his own recording and band, African Force. The first African Force album is pretty similar to Kuti’s music though it relies a lot less on the guitar and includes horn arrangements featuring trombone and baritone saxophone. It’s a strong record that will stretch the ears of listeners who haven’t heard it before, but even more amazing is the live followup recording Palanquin’s Pole.

Palanquin’s Pole features Baker with a group of percussionists and there is no real non-percussion instrumentation to speak of–some vocals and a little marimba. You can compare the version of ‘Brain Damage’ here with that on African Force. It’s a different track without the horns, but it’s definitely the same groove, and Baker is clearly the driving force at its center. With its drum-forward emphasis, Palanquin’s Pole is the Love Supreme of drum albums, recalling the work of Mickey Hart’s Planet Drum and Rhythm Devils and presaging world drum techno jam wizards Tabla Beat Science. Both of the African Force albums are well worth searching out and the live set is really a unique drum record for fans of the genre.

Following the failure of his Nigerian studio as the 1980s beckoned, Baker, who had relapsed into his heroin habit 29 times by his own count, went to live on an olive farm in rural Italy. Here, in the Meditteranean sun, he was able to kick his habit for good and he reportedly played little music during this time.

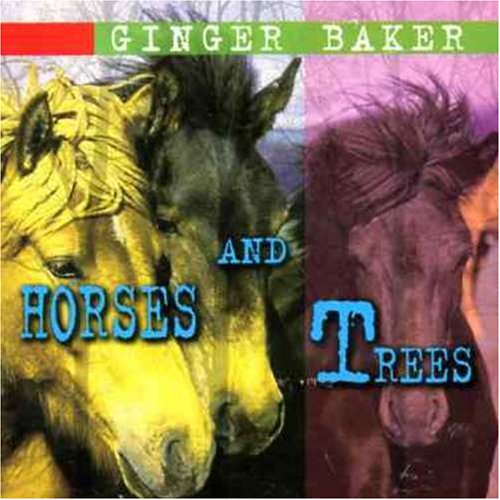

In 1986 producer Bill Laswell coaxed Baker into the studio to play with Public Image Limited, and it’s very recognizably Ginger playing. More importantly, he returned to recording his own projects with Laswell on board as producer. Horses and Trees (1986) and Middle Passage (1990) both feature Baker with Laswell, guitarist Nicky Skopelitis (who worked with Laswell as a member of the Golden Palominos), Jah Wobble, and Parliament keyboard player Bernie Worell.

Horses and Trees features Skopelitis’ Greek folk-influenced guitar work on almost all tracks, with Laswell providing some steel guitar. “Dust to Dust” is a country and western by way of Santorini groove composed by Baker, while Satou makes ample use of a group of African and Brazilian percussionists as well as some of Worrell’s otherworldly keyboards.

Middle Passage is similar, but features more keyboard atmospherics and less guitar, as Skopelitis is only featured on two tracks. World music sounds are still the vibe but there is a definite techno edge to the music, very much in line with Laswell’s other projects. But no matter–Baker is able to slide into the drum chair and provide exactly what the music needs regardless of its prevailing style.

Baker created a very different environment with his collaborations with Bill Frisell and Charlie Hayden. The group recorded the albums Going Back Home (1984) and Falling Off the Roof (1986). This was a straight-ahead jazz trio that played a combination of original compositions and standards like Thelonious Monk’s ‘Straight No Chaser’ and ‘Bemsha Swing.’

There’s a lot of energy on tracks like ‘Ramblin” and the group sounds like they’ve been playing together for years. Bill Frisell offered these thoughts about the recordings to Rolling Stone in the wake of Baker’s death:

“…We set up and we start playing, and suddenly it was just like three guys playing, and he just started smiling. It’s just incredible what music does. However many years ago this was — 25 years, I can’t believe it’s that long — it was just this instant bonding; an understanding [and] the way music just breaks down any kind of barrier. And there was this joy. We were really just playing, picking tunes like “Straight No Chaser.” And Ginger was so generous. We played his tunes; he played our tunes. And it just felt real honest in that way.”

The last Baker collaboration I want to mention is the 2013 release No Material, an improvisational free jazz outing with Baker and associates Nicky Skopelitis and Jan Kazda (who played on African Force) teaming up with free jazz musicians Sonny Sharrock and Peter Brotzmann. The group plays nearly 2 hours of improvisational pieces that run the gamut from face-melting free jam to psychedelic drone to scorched Earth fusion that recalls Miles Davis’ 1973-74 bands.

Baker was one of the greatest musicians out there, and though he could be challenging to work with at times, he managed to get along great once the band was playing or the tape was rolling. He’ll always be remembered as a rock artist but for those who like to listen to music that goes a bit further out, he’s been on the cutting edge for his whole life. Ginger Baker was that true rarity: a musician who remains relevant for his entire life regardless of whether he’s on the charts or not.